Culture

This is the essence of China, a civilisation that has withstood the test of time for over five millennia and continues to inspire the world today. Its enduring virtues and resilience were shaped and strengthened by great sages like Laozi and Confucius, whose teachings have guided the Chinese people through both prosperity and adversity.

Within this grand civilisation lies a small yet remarkable community, Putian, whose people are better known in the Nanyang as the Hinghua. Over time, they too have evolved, developing their own unique culture and traditions. These values form an invisible bond that unites the clan across generations and geographies, allowing them to find their place in the region, proudly known as the Hinghua People.

Source: Jason Ong and 林洲

Source: Jason Ong and 林洲

Culture and traditions evolve gradually -- often over millennia -- before a people can confidently say, “This is who we are, and this is what we do as a people.”

The Hinghua people are no exception. Over thousands of years, Hinghua culture has developed deep roots, grounded in virtues closely aligned with Confucian teachings -- namely Ren (仁), Yi (義), Li (禮), Zhi (智), and Xin (信) (Wuchang, 2009). Among the foremost virtue is filial piety.

Filial Piety

Filial piety lies at the very heart of Hinghwa family culture, it is the glue that binds generations together. Afterall it is considered the foremost virtue in Chinese culture.In much of my writing, I have been privileged to encounter many remarkable individuals who continue to uphold this cherished tradition. This value is not only central to the Hinghwa community, but also forms the foundation of Chinese culture across the entire nation.Each Chinese New Year, the world bears witness to the largest annual human migration, as countless sons and daughters journey home to pay respects to their parents. This joyful reunion reflects a deep-rooted cultural reverence for elders. Even the departed are not forgotten; families visit ancestral tombs to honor their loved ones, reaffirming that love and respect transcend death.It is this unwavering devotion to one’s roots that has sustained Chinese culture through the millennia. We never forget those who gave us life, nor do we abandon those who nurtured us with tireless care so we could become valuable members of society.In Chinese, to be called a “不孝顺的孩子” (an unfilial child) is a grave condemnation. Such a person is often despised and scorned by society.

Cultural Values

These values laid the foundation for a community once celebrated as a Centre of Culture and Literature, where intellectual pursuit, moral integrity, and artistic refinement were deeply cherished.

As Hinghua traditions evolved, they naturally intertwined with religious beliefs, giving rise to a rich tapestry of folk practices influenced by Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, each leaving a profound mark on the others. This blending of philosophy and spirituality continues to shape the Hinghua worldview today.

As a result, most Hinghua identify as Taoist or Buddhist, though a small but significant number have embraced other faiths such as Christianity or Islam.

What truly binds the Hinghua people, however, is their shared ancestry in Putian, their unique language, and the distinctive cuisine they continue to enjoy and celebrate. This common heritage, rooted in virtue, language, and tradition, has allowed the Hinghua community to endure through the centuries and continue thriving across generations.

Source: Jason Ong

Hinghua Language

The Nanshan Guanghua Temple in Putian is said to be the first Buddhist temple built during the Chen Dynasty. Evidence of when the Hinghua language became part of the Putian dialect can be found on the inscription in the temple.

The integration of the Han Chinese with the Minyue ethnic group (闽越族) and the Baiyue nationality group (百越民族), whose Baiyue language (百越语) influenced the development of various local languages, played a significant role in shaping the Hinghua language. Prof. Chen explains:

"兴化方言形成过程中融合了古代百越族的语言成分,因此,兴化方言的形成也有民族融合的原因。兴化方言之所以能成为闽方言中的一个独具特色的次方言,与其独特的地理环境因素是分不开的。兴化地区在地理位置上,处于闽东地区与闽南地区的交界处,兴化方言是在闽东方言与闽南方言的磨合与碰撞的基础上,形成了自身特色的混合性方言" (Prof. Chen, C. Y.).

English Translation from Baidu

In the process of forming the Hinghua dialect, the language components of the ancient Baiyue ethnic group (百越族) were integrated. Therefore, the formation of the Hinghua dialect also has the reason of national integration. The reason why the Hinghua dialect can become a unique subdialect in the Min dialect is inseparable from its unique geographical environment. The geographical position of the Hinghua area is at the junction of eastern and southern Fujian. Hinghua dialect is a mixed dialect with its own characteristics based on the running in and integration between the eastern Fujian Dialect and the southern Fujian dialect.

The integration was for the better, as Prof. Chen adds, citing linguist Li Rulong (李如龙), who explains that the Han Chinese brought a superior culture to the central plains and the Putian/Fujian area, which greatly influenced the local communities. This language evolution is not isolated but an inevitable process when different groups of people interact over a prolonged period.

Although the Hinghua language is believed to have evolved from the Central Plains during the era of the Western Han Dynasty, the earliest historical record of its existence dates back to its use in the Puxian opera during the Tang Dynasty. Unlike the English language, which emphasizes grammatical rules, Hinghua focuses on sound, maneuvering around eight distinct tones.

It is a fascinating language, believed to have been the imperial language in ancient times, especially during the Tang and Song Dynasties, as many prominent Hinghua individuals from the region and China were descendants of the Tang Dynasty emperor. It was also thought to be an official language due to the large number of scholars from Putian during these two dynasties. However, there is no definitive evidence to prove or disprove either of these assumptions.

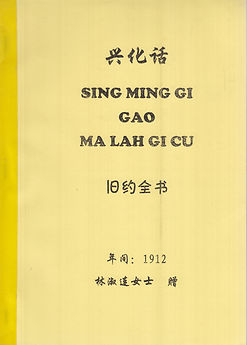

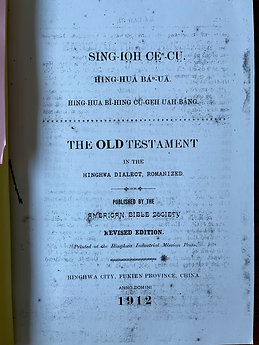

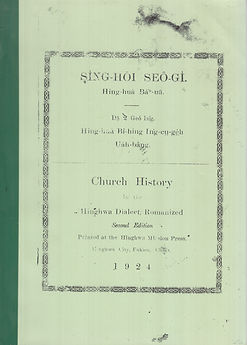

The Hinghua people came close to having a written language when Methodist missionary William N. Brewster (蒲鲁士) translated part of the Bible into the Romanized Puxian dialect in 1890, known in Hinghua as Hing-hua̍ báⁿ-uā-ci̍ (興化平話字; Xīng huà píng huà zì).

The earliest evidence of the Puxian dialect is said to be the inscription found in the Nanshan Guanghua Temple, Putian (南山光华寺, 莆田), which has existed since the Sui Dynasty. The temple got its present name in 976 AD during the reign of the Song Dynasty.

The Puxian dialect (莆仙方言) or Hinghua dialect (兴化方言) belongs to the Bohai or Mǐnhǎi (闽海; coastal areas of Fujian and Southern Zhejiang) dialect groups. According to the history of Puxian, the Puxian dialect was spoken by the Hinghua Jun (兴化军) and Hinghua Fu (兴化府). Therefore, the Puxian dialect is synonymous with the Hinghua dialect (Wang, H. n.d. (a)). As the Hinghua Jun controlled a large area, it had a profound influence over the people within its domain. As Wang, H. (n.d. (b)) states:

莆仙方言属汉语方言系闽海方言群,因莆仙历史上同属于兴化军、兴化府,所以,莆仙方言也称为兴化话。

Pú xiān fāngyán shǔ hànyǔ fāngyán xì mǐn hǎi fāngyán qún, yīn pú xiān lìshǐ shàng tóng shǔyú xīng huà jūn, xīng huà fǔ, suǒyǐ, pú xiān fāngyán yě chēng wèi xīng huà huà.

In China, the Hinghua language is spoken mainly by people from Putian and Xianyou, hence it is also known as the Puxian language (Kele, 2006b). However, it is also spoken by people in other nearby villages or counties, such as Fuqing Xincuo (福清新厝), Jiangdou (江兜), Jiangyin (江阴), Yidou (一都), Dongzhang (东张), Dongau (东澳), Jingyang (镜洋), Yinxi (音西), and Hui'an Tuling (惠安涂岭) and Huibei (惠北). It was also spoken in the south of Yongtai Wutong (永泰梧桐) and west of Qikou (嵩口以西). This was because Fuqing County, together with Putian County and Xianyou County, were formerly part of Xinghwa Jun. Including those from outside China, there is an estimate of about 5 million people who speak the Puxian dialect (Wang, H. n.d. (c)).

Hinghua Language Bible

Source: Jason Ong and Kapitan Frankie Nee

Interested in learning the Hinghua language?

Start your journey in the Learning Hinghua section.

Arts

Southern Shaolin Temple

(南少林寺)

Southern Shaolin Temple (南少林寺)

Source: 雷丹雰

The most famous Chinese Zen Buddhist temple is the Shaolin Monastery (少林寺), renowned for its unique integration of faith and martial arts, specifically, Shaolin Kung Fu. Originally built in 557 during the Southern Dynasty, the temple was first known as Linquanyuan (林泉院) (Weng, 1994, p. 1205).

According to tradition, it was founded by a holy man named Ta Tsun-shen. In more recent times, archaeologists confirmed that the temple in Putian was the first of its kind built in Southern China.

The martial prowess of the Shaolin monks became legendary, particularly after they came to the aid of Emperor Li Shimin of the Tang Dynasty, rescuing him from his enemies. However, the temple's fortunes declined during the turbulent Qing Dynasty. The monastery was razed, and many monks were killed. Of the 18 monks who initially escaped, only five survived; the others died in later battles.

These five survivors would go on to inspire what became known as the Triad or secret society, whose mission was to fight against injustice.

Since then, the Shaolin Temple has transformed into a hub of cultural activity, focusing on meditation, education, and Traditional Chinese Medicine. This evolution was made possible through a timely initiative by the Chinese government to preserve and promote the temple as a vital part of Chinese heritage and culture.

In 1986, a team of academics and archaeologists in Putian uncovered relics linked to the Shaolin Temple’s history and its key historical figures. Then, in 1992, the People’s Government of Fujian Province officially approved the temple’s reconstruction, marking a new chapter in its long and storied history.

Arts and Crafts

Puxian is world-famous for its woodcarvings, with around a thousand companies in the industry. These carvings -- often made from high-quality Agarwood -- can range in price from just a few dollars for a small piece to tens of thousands for magnificent works typically displayed in hotel lobbies.

Master craftsmen spend years perfecting their skills, and precision is the hallmark of the Hinghwa people.

One notable company in this field is Pútián Shì Xīn Zhōu Chuánméi Wénhuà Yǒuxiàn Gōngsī (莆田市鑫洲传媒文化有限公司), which specializes in Agarwood handicrafts (沉香文玩经营). The owner, Lin Zhou (林洲), is a trustworthy and talented young man known for his dedication to quality and craftsmanship.

A tribute to the

GUARDIAN OF HINGHWA HERITAGE

Lin Zhou (林洲)

(莆田市鑫洲传媒文化有限公司)

Lin Zhou (林洲) hails from Meiling, Fenglin Village, Wutang Town, Hanjiang District, Putian City (莆田市涵江区梧塘镇枫林村梅岭). A 35-year-old family man, he is married to Wu Haiyan (吴海燕), and together they have a son, Lin Jia Jun (林嘉骏), and a daughter, Lin Jia Xin (林嘉欣).

He is the owner of Putian Xinzhou Media & Culture Co., Ltd. (莆田市鑫洲传媒文化有限公司), a business devoted to agarwood handicrafts, a craft rooted in tradition, patience, and artistry.

I had only known Lin Zhou for less than a month through WeChat before I visited Putian in September 2024 on a 10-day study tour. Yet, his hospitality during my stay was truly beyond words.

Quite literally, he took care of everything, organizing my visits to 40 historical sites, accompanying me every step of the way, and covering all expenses without hesitation. At the end of the journey, I offered to repay him, but he gently refused. Feeling awkward, I asked, “Why?” He smiled and simply said, “I’m just happy to do my part to promote Putian and the Hinghwa culture.”

On the eve of my departure, he hosted me for tea and dinner. Afterward, he drove me back to my hotel, nearly 100 kilometers from his home. It wasn’t the first time. He had also picked me up upon my arrival, and over the course of the tour, he must have driven close to 1,000 kilometers. The sheer extent of his generosity left a deep impression on me, especially since he never once accepted anything in return.

As his car pulled away from the hotel that night, I bowed, deeply, silently, and with heartfelt gratitude.

To my surprise, he later messaged me to say that he had cried when he saw me bowing. It was then that I realized something quietly profound:

Throughout my entire trip, I had only bowed to Mazu, to Cai Xiang, to Confucius… and to Lin Zhou.

Puxian Opera

Source: Jason Ong and 林洲

Since the Tang Dynasty, Puxian opera has served as a vibrant platform for showcasing the rich culture and language of the Hinghwa people. Its popularity has endured through the centuries and continues to thrive in modern-day China.

One of the most renowned performances is the Mulian Play, also known as Mulian Saving His Mother. This play is especially popular during the Seventh Month Festival, when elaborate ceremonies are held as part of grand celebrations in many Hinghwa temples.

The practice of Li (礼, propriety) and Yue (乐, music) is deeply embedded in Hinghwa tradition, fostering harmony not only among the living but also with the departed and wandering souls.

As part of this tradition, temples often organize grand festivities, including opera performances, to honor the deities and appease spirits.

However, opera shows have always been expensive -- even in earlier times. For example, a temple along Jalan Tenteram in Singapore recently hosted a three-day festival featuring opera performances and communal dinners. It took nearly two weeks to set up the stage and tents, and another week to dismantle them -- all for just three days of celebration. The cost was enormous. Yet, the show must go on.

For practical reasons, some temples -- and even individual households wishing to entertain their deities at home -- may choose to host puppetry shows instead. These performances offer a more affordable, yet equally meaningful, alternative.

As shown in a recent video from Putian, puppetry remains a captivating form of cultural expression even today.

In Singapore, the Hinghua Sin Hoe Ping Puppet Troupe, owned by Yang Lai Hao, is the only Putian-style puppet troupe in the country.

Both opera and puppetry have long been beloved by the Hinghwa people, as the performances bring to life the stories of ancient heroes and cultural values.

Today, these traditional performances are still held in temples during festival seasons and are performed in the Puxian language, helping to preserve the cultural identity of the Hinghwa community.

Puxian Puppetry

Hinghwa Puppetry at Kiew Li Tong Temple in Putian.

Source: Jason Ong and 林洲

The Bang Structure

One might wonder how early migrants managed to survive in such a harsh environment, surrounded by gangs and violence. The answer lies in a powerful bond known as 帮结构 (Bang Structure), or the "support structure."

When these migrants first arrived in Singapore, they brought with them a deep-rooted culture of camaraderie from their hometowns.

Bound by an invisible thread of shared heritage, they remained united as a community. This unspoken bond, inherited from their native villages in Putian, kept them closely connected wherever they settled in Nanyang (Southeast Asia). Naturally, they began forming groups, much like the saying, “birds of a feather flock together.” These groups went by various names, but were commonly referred to as Bang Structures (帮结构) or Associations.

Most early refugees and migrants arrived in Singapore with little more than the clothes on their backs. Many had no family or acquaintances to rely on. In response, ethnic communities began forming their own self-help organisations to support fellow clan members in adjusting to their new environment. This system became known as the bang (帮), meaning “help” or “support.”

The Bang Structure was especially vital for new arrivals who needed help finding employment, housing, and protection. It also provided emotional and practical support in times of crisis, such as illness or death. Members of the Bang Structure would take on communal responsibilities, including arranging funerals and caring for the sick or elderly.

Over time, these networks developed into more structured associations, complete with elected officials, expanding their role from simple survival to community leadership and representation.

List of Hinghua Associations

Singapore

Over time, the people became more organized, forming associations to better represent their interests and support their communities. As noted, these gatherings were heavily influenced by Guanxi culture, a deeply rooted social system in China that emphasizes relationships and personal networks.

In Chinese society, Guanxi begins within the immediate family, then extends to relatives, close friends, and fellow villagers. It is not customary to build close connections beyond this invisible circle. While modern life has brought many changes, cultural traditions often evolve slowly -- if at all. This is why the saying still holds true: “Birds of a feather flock together.”

The following is an overview of how the Bang Structure gradually evolved over time.

-

Hin Ann Huay Kuan (兴安会馆) (1920).

-

Phor Tiong Koh Peng Association (新加坡莆中高平公会)(1947).

-

Singapore HockPoSian Association(新加坡福莆仙公会)(1948).

-

Singapore Putian Association (新加坡莆田会馆) (1956), formerly known as Nanyang Pho Chen Huay Kuan(南洋莆田会馆).

-

Singapore Kang-Tau Ong Clansmen Association (新加坡江兜王氏公会) (1974).

-

Singapore Puxian (Hinghua) Network (莆仙同乡联合会) (2019) formerly known as Puxian (Singapore) Entrepreneurs Network Ltd.

Trade/Occupational

-

Singapore Cycle & Traders Association (新加坡车商公会)(1932).

-

Taxi Transport Association (新加坡交通德士公会)(1946).

-

Singapore Trishaw Owners Association (截客三轮车车主公会)(1947).

-

Singapore Bicycle Dealers Association (新加坡自行车商公会)(1952).

-

Singapore Motor Tyre Dealers Association (新加坡汽车胶轮商会) (1952).

-

Singapore Cycle and Motor Workers Union (新加坡车业职工联) (1955).

Source: Cheng, L. K. (1993, p. 46)

Updates: Jason Ong

Business Traditions

Hinghua Taichi

Source: Jason Ong

"I say nothing, I see nothing, and I hear nothing, yet everybody knows."

This was one of the most intriguing strategies I picked up while working as a delivery boy for Lian Hoe Motor, which was then located on Dickson Road.

Among spare parts traders, silent communication was an art, especially when it came to credit, trust, and reputation. Newcomers to the trade often began with a small sum of capital, offering it to wholesalers as a gesture of goodwill. In return, they were typically granted credit terms ranging from 14 to 30 days, depending heavily on clan affiliation and personal relationships.

Credit was most readily extended to those within the same clan network. Outsiders, while not completely excluded, had to work harder to earn trust. When they did, they might be offered temporary credit, but usually for smaller amounts, and always with the understanding that previous purchases had to be cleared before the next batch would be released.

Bad debts within the same clan were rare. The reason? The social consequences were serious. If someone defaulted, the entire clan would distance itself, effectively cutting that person off from doing business within the community. Although these cases were few and far between, word always got around -- without a single word being spoken.

Here’s how the system worked:

Let’s say ‘Ah One’ issues an open (uncrossed) cheque to ‘Ah Two’, and it bounces. Now, instead of banking the cheque, Ah Two decides to use it as payment to another trader, let’s call them ‘Ah Three’. Sensing something’s amiss, Ah Three also refrains from cashing it and passes it along to someone else.

By the time the cheque reached the end of the merry-go-round, the entire clan network would become aware that Ah One issues bad cheques.

Naturally, credit to Ah One dries up very quickly. His only remaining option? Cash-only transactions. In a trade that runs on trust and relationships, this shift often spells the end of a business.

---

Note: An open or uncrossed cheque is a negotiable instrument that can be endorsed and transferred to another party as a form of payment. The bearer simply signs and stamps the back of the cheque before passing it on.

Lions and Dragons

The symbols of the lion and dragon have been integral to Chinese culture and landscape since the earliest days of Chinese civilization.

Both are powerful icons of protection, authority, and good fortune. Dragons, revered as divine beings, symbolize imperial power, strength, and the emperor’s supreme authority. Lions, often depicted as guardian statues, are believed to ward off evil spirits. They also represent power and protection for buildings and their inhabitants.

For these reasons, emperors' robes were adorned with dragon motifs, while their palaces were flanked by pairs of lion sculptures at the entrances. Similarly, palace rooftops were often decorated with dragon figures and other symbolic creatures facing the four corners, serving both as architectural embellishments and spiritual guardians.

Top Left: Student dressed as a Qing Dynasty emperor with dragon motifs at the Summer Palace. (Photo credit: Jason Ong).

Top Right (Top): A lion sculpture at the entrance of a Sauce Factory (Photo credit: Ronni Pinsler).

Top Right (Middle): A row of lions and a dragon perched along the roof corner of the Summer Palace.

Top Right (Bottom): One of the giant lion sculpture guarding an entrance within the Forbidden City, Beijing. (Photo credit: Jason Ong).

Arrangements by Jason Ong

Mystery of the Lion at a entrance of a sauce factory

Some 55 years ago, I was carrying my nephew, barely one or two years old, as we walked past a sauce factory. Like many adults, I enjoyed pointing out animal figures to young children, so when I saw the lion sculpture at the entrance, I instinctively pointed to it and said, “Lion.” My nephew looked up and suddenly shuddered. Puzzled by his reaction, I went home and told my mother about it.

My mother, a native Hinghua speaker, once said something in her dialect that stuck with me for 55 years. Referring to the lion, she simply said, “ook ornh”. I didn’t understand what those words meant at the time, and I never thought to ask. It wasn’t until decades later, when I began researching and writing about the history and stories of the Hinghua people, that I found myself returning to that moment, and to those two unforgettable words.

During my study tour to Putian in September 2024, I posed the question to many: the young, the elderly, even the eldest of the elders. Strangely, none of them knew what “ook ornh” meant. Then, around Chinese New Year, my attention was drawn to the character “旺” (wàng), which I kept seeing on pineapples and festive decorations during my walks. In Chinatown Complex, I met a shopkeeper from Putian and took the opportunity to ask her. Without hesitation, she said, “ook ornh.” She explained that it had something to do with blessings and prosperity.

While that answer gave me a linguistic connection, it didn’t fully explain my nephew’s reaction all those years ago. Still curious, I brought the question to a Hinghua chat group. That’s when a breakthrough came. Mr. B. J. Tay, a fluent Hinghua speaker, suggested that my nephew might have sensed the “aura” around the lion sculpture.

As I reflected further, the picture became clearer. The “aura” Mr. Tay referred to was likely the positive energy, "Chi", believed in Chinese metaphysics to be emitted by guardian figures like lion statues. In traditional Chinese culture, such lions are not just decorative, they are believed to offer powerful protection and attract prosperity.

Putting everything together, I came to realise that the lion sculpture at the sauce factory may indeed possess a kind of mystical presence, or, from a Christian perspective, it may well have been a powerful Guardian Angel.

I vividly remember how the sauce factory remained miraculously untouched, even as a massive fire swept through the living quarters just beyond its walls. Despite the streets outside often being plagued by gang activities and violence, the factory owner's children were remarkably shielded from these negative influences.

It is no surprise, then, that they all grew up to become successful individuals, some even rising to prominence in their respective fields.

Perhaps, just perhaps, the lion, or what Christians might see as a Guardian Angel, had been watching over them all along.

---

If I may add, in my long search for the meaning of a word that had lingered in my memory for decades, I eventually discovered it was the character “旺” (wàng). By some strange twist of fate, or perhaps divine design, I found myself unknowingly staring at this very character, emblazoned as the giant logo of a café at the airport while waiting for my flight.

It felt as though the angels, with a touch of humor, had made sure that no matter how myopic I was, I wouldn't miss it this time.