道法自然

LH: Lao Zi

Source: Ai

RH: Kong Zi

Source: Jason Ong & 林洲

Three Sages of Ancient China

There were many sages and heroes in ancient China, but three of them have withstood the test of time and laid the foundation for Chinese education and culture. Ironically, all three of their names end with the character "子" (zǐ), which holds profound meaning, symbolizing purity, humility, new beginnings, and greatness. Thus, I refer to them as "The Three Sages" of ancient China (古代中國的三子). They are:

• Lao Zi (老子) – Philosopher, Founder of Daoism

• Kung Zi (孔子) – Philosopher, Educator

• Sun Zi (孙子) – Philosopher, Military Strategist

Sun Zi is still revered today as a brilliant military strategist. In his foreword, American war veteran General David Petraeus -- who has 37 years of military experience and served as CIA director -- states, "The Art of War by Sun Zi has rightly become one of the world's most influential books on military strategy." General Douglas MacArthur, too, is said to have had one of these books in his collection.

Indeed, Sun Zi's Art of War is a seminal work that every serious military strategist would have read.

However, of the three, Lao Zi and Confucius have had the strongest influence on the Hinghua people.

Lao Zi is often considered the teacher, with Confucius as his student, who went on to teach many others. Yet both Lao Zi and Confucius are revered as sages who laid the intellectual and philosophical foundation of Chinese culture.

The Dao that can be told

is not the eternal Dao.

The name that can be named

is not the eternal Name

(老子; Lǎozi).

This loaded statement is presented in simple words, but with a wisdom that goes beyond human understanding.

Lao Zi (老子) was the founder of the philosophy of Dao (道家; Daojia), which is distinct from the religious aspect of Daoism (道教; Dàojiào) founded by Zhang Daoling.

Lao Zi’s main interest was living harmoniously with nature. With his brilliance and connections to the imperial family, he chose to leave behind his wisdom to a farmer who had begged him to share his knowledge before the sage withdrew to his hermit kingdom. The writings he left behind became known as the world-famous philosophy – The Way (道德經; Dao De Jing).

In this work, he explored the mysticism of the cosmos, the balance of Yin and Yang (阴阳), Wu Wei (无为), and the treasures of Compassion (慈; Cí), Frugality (俭; Jiǎn), and Humility (谦逊; Qiānxùn). At its core, the philosophy emphasizes living harmoniously with nature and allowing things to flow naturally.

In comparison to Buddhism and Confucianism, Taoism is more focused on the salvation of humanity, the soul (spirit), and health (Liu, D. J., 2011).

In Taoist spirituality, the existence of 'Supreme Being' (God) is recognized, and they refer to this being as Shang Di (上帝) or Shen (神). The concept of Shang Di reflects the Taoist belief in a superior being in heaven (天堂), in contrast to the earthly emperor, whose mandate to rule was believed to come from this divine entity.

The realization of the power of Shang Di led to the construction of the Temple of Heaven (天坛) by Emperor Yongle in the 15th century. This temple was built to worship the almighty, and succeeding emperors would lead the annual worship ceremonies at the Altar of Heaven, where the emperor himself acted as the chief priest. The temple is located at: 1 Tiantan E. Rd, Dongcheng Qu, Beijing, China, 100061.

The ancient Daoists observed that everything in the universe, whether matter or life, has an equal opposite, and all things are interconnected and must be balanced. This is represented by the Daoist symbol. In particular, the relationships of the five elements -- fire, water, earth, metal, and wood -- form a cornerstone of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Physicians in TCM believe that illnesses arise from imbalances in Yin and Yang (阴阳). Lin (2016) states:

The Yin & Yang theory permeates all aspects of the theoretical system of TCM. The human body is an integrated whole. All its tissues and structures are organically connected and classified as two opposite aspects -- Yin & Yang (阴阳).

The balance of Yin & Yang (阴阳) is essential for good health (Ong, 2019). In health, Taoist theory also relates to San Bao, which includes: (i) Qi (气), (ii) Jīng (精), and (iii) Shén (神) (Kimmel, 2017). The term Shén (神) indicates the Daoist belief in the interconnectedness of mysticism and humanity.

Taoism as a religion will be discussed in another section relating to the beliefs of the Hinghua people.

Temple of Heaven

Source: Jason Ong

Wu Wei

無為

(Action without Action)

The concept of ‘Inaction’ (無為; Wúwèi) -- also known as ‘无为’ -- is interpreted as ‘action without action.’ This means allowing things to take their natural course.

However, this does not imply doing nothing and expecting everything to fall into place. On the contrary, to achieve ‘Wúwèi’ (無為), one must engage with wisdom.

For example, if it is known that a severe typhoon is approaching, the logical course of action is to evacuate all people from the area -- including villages, towns, or cities, if necessary. While the storm will eventually pass, doing nothing is an invitation to disaster.

Wúwèi (無為) can also be applied to the Art of Government or ‘statecraft’, where the ruler governs without exertion, yet the people follow as though they instinctively know that it is the right thing to do.

This type of leadership was evident in several later dynasties.

In such a system, everyone acts with a conscience toward the state's well-being. Liu, D. J. (2011), a professor at Shandong University, states:

"According to Laozi, we should be quiet and passive so that things will take their natural course. We should not interfere with or try to steer things in a direction we have planned."

Handling Challenges with Wúwèi

There are three major challenges in life: competition, temptation, and the fear of death.

In competition, we are often pushed to our limits in the pursuit of being better than others. Yet, the expectation to win is not always met, and disappointment can follow. This is where the practice of Wúwèi may offer a different perspective. Rooted in the philosophy of effortless action and alignment with the natural flow of life, Wúwèi encourages us to accept outcomes as they come. It reminds us that sometimes, we must learn to let go, especially of the weight of perceived failure.

By doing so, a person can feel more at ease, and ultimately, the result is a happier mindset.

As for death, the fear of it often leads to misery. In this case, Wúwèi suggests ‘letting go’ of everything attached to the earth, which can lead to peace replacing the agony associated with death.

This reminds me of a young lady, only 18 years old, who was stricken with kidney failure and didn’t have much time to live. As she lay in her hospital bed, she shared with an elderly man nearby how miserable she felt, being so young and having so much to look forward to. The elderly man gave her this advice: "You must learn to let go." She tried and succeeded. She felt much better as her life slipped away.

When Laozi (老子) passed away during the Zhou dynasty around 479 BCE, he left behind a legacy that became deeply ingrained in Chinese culture -- a legacy that has withstood the test of time.

His most famous student, or contemporary, was Confucius, who had consulted Laozi and observed how he conducted certain rites and practices of his philosophy.

Confucius

(孔子; 550 BC – 479 BC)

Source: Jason Ong & 林洲

"This photo was taken at the top of the 49 steps at the largest Confucius Temple in Putian."

Confucius was born in the Lu State (魯州), which is now modern-day Qufu city in Shandong Province.

His main interests were in education, humanity, and the structure of government. As a young man, Confucius learned the traditions and the art of ceremonies from his master, Laozi. Upon returning to his home state, he compiled his observations into several books.

These works became known as the Four Books and Five Classics (四書五經). The Four Books were:

-

Analects of Confucius (論語)

-

Mencius (孟子)

-

Great Learning (大学)

-

Doctrine of the Mean (中庸)

The Five Classics were:

-

Book of Rites (礼记)

-

Book of Songs (诗经, Ode and Poetry)

-

Book of Documents (尚书)

-

Book of Changes (易經, I-Ching)

-

Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋季节)

Confucius hoped that his students would become learned individuals who possessed high morals, integrity, and practical skills -- qualities that would enable them to realize his vision of a better society.

His book, The Analects of Confucius, primarily records his discussions with his students. In it, he imparts his teachings on the concepts of benevolence and ritual propriety (Tang, 2011).

Confucius’s ultimate goal was to eliminate corrupt imperial officials and establish a government rooted in righteousness. He envisioned a society led by virtuous individuals, capable of promoting harmony and good governance. His teachings on the Mandate of Heaven (the right to rule) had a profound influence on several emperors who followed him, as they embraced his ideas with great success.

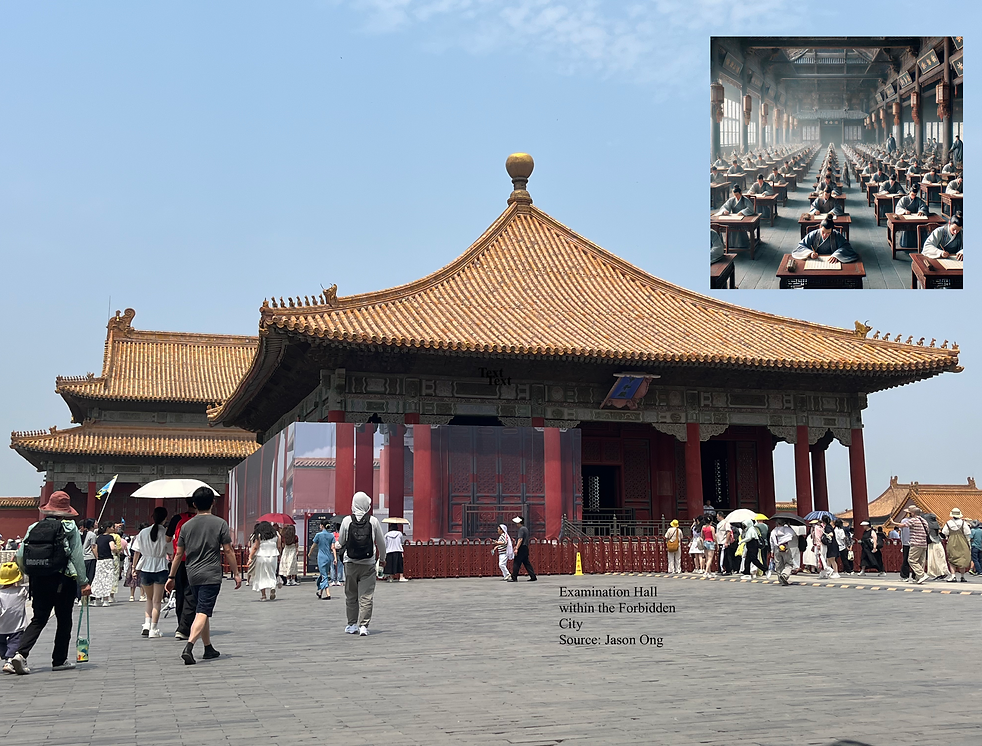

Confucius’s works have provided a solid foundation for Chinese culture that endures to this day. Confucianists aspire to be wise, powerful, and virtuous. Their highest ideal is to offer meritorious service, create exceptional writing, and uphold high moral standards (Liu, D. J., 2011a). This philosophy deeply influenced the Hinghua people, many of whom became imperial scholars and high-ranking officials during the Tang and Song Dynasties. The impact of Confucianism also extended to the Nanyang region, carried by migrants during and after the fall of the Qing Dynasty.

During the Tang and Song Dynasties -- two of China’s golden ages -- the emperors practiced the teachings of Li (礼, ritual propriety) and Yue (乐, music), and the people eagerly anticipated each festival. These celebrations, which included food, music, and dance, were not just joyous events but also ceremonies filled with meaning.

Whether it was celebrating the Lunar New Year, honoring festivals at temples, worshiping ancestors, or observing the Ghost Month festival, each occasion was a ritual of joy and reverence.

Largest Confucius Temple in Putian

Source: Jason Ong & 林洲

Source: Ai (2025) Chinese festivals

Joyful Festivals: Li & Yue in Action

Just like Wu Wei, the term Li (礼) is akin to a diamond with many facets, each reflecting a different spectrum of light. This is because Li (礼), as in 礼仪 (Liyi, etiquette), encompasses many aspects, such as filial piety, ancestor worship, respect, and social behavior. It governs the way we address elders, speak, walk, dress, eat, and drink. It also outlines how rulers should treat the people and how people should respect authority, both at home and in public.

On the other hand, Yue (乐) refers to music (音乐) and joy (快乐). Soothing music nourishes the soul, bringing people together to celebrate in a peaceful and harmonious environment that fosters a sense of reverence. Professor Li Xue Qin from Tsinghua University succinctly captures the significance of Li and Yue when he states:

"The important function of Li and Yue was to bring about peace and harmony, even amongst people with many differences. For the Chinese, Li and Yue were essential tools for educating people, as their purpose was to promote harmony and peace" (Li, X. Q., 2011c).

In the realm of education, Confucius teaches: “The superior man is strong and untiring. Thus, the superior man, who has a breadth of character, carries the outside world.”

This teaching resonates deeply with the Chinese people, motivating them to strive to become better individuals who contribute significantly to the prosperity of the Chinese nation. The qualities of a superior man -- strength, perseverance, and character, are ideals that the Chinese people aspire to embody.

World's First Meritocratic System